After that peak in November 1994, yields steadily fell before bottoming at 0.51% in August 2020 – and it was a similar story in the UK after yields on the 10-year Gilt peaked at 9.03% on September 1994, yields fell steadily to 0.08% in August 2020 (which was when we were all enjoying the lifting of the lockdown restrictions and taking advantage of the government’s ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme).

Today, the 10-year Gilt yield is 4.04%, having risen by a massive 1.99% during the valuation period, while the US equivalent has also climbed strongly and currently stands at 3.76%.

As bond yields have risen sharply, bond prices (which move inversely to yield) have fallen sharply.

Bond returns (using the IA Sterling Corporate Bond fund index as an example) are down a staggering 20.35% since the start of this year, while the price of a 30-year US government bond has lost just over one-third of its value.

If the IA Sterling Corporate Bond fund index ends 2022 where it is today, it would be the worst performance since the index was created – far worse than the 11.63% decline in 1994 or the fall in 2008 (the global financial crisis) of 9.67%.

These higher yields haven’t simply hurt bond prices and the cost of our borrowings (hence why we have seen the cost of a fixed-rate mortgage increase dramatically); higher yields will lower equity prices as the value of the discounted future cash flows will be lower – hence why the performance of the major equity markets (such as the Dow Jones, S&P 500 and the FTSE-100) have been negative over the valuation period.

The main cause of these higher yields and lower equity prices is that the world’s central banks have accelerated their size and pace of monetary tightening to tame inflation.

Whilst we didn’t think yields would rise quite as sharply as they did, we did expect interest rates to rise and as such we held underweight positions in fixed-income securities within the ‘Long-Term Growth Element’ (meaning we held less than the benchmark weight) – and while it is a small consolation, this underweight position has meant that the Cautious, Balanced and Adventurous portfolios have performed much better than they otherwise would have.

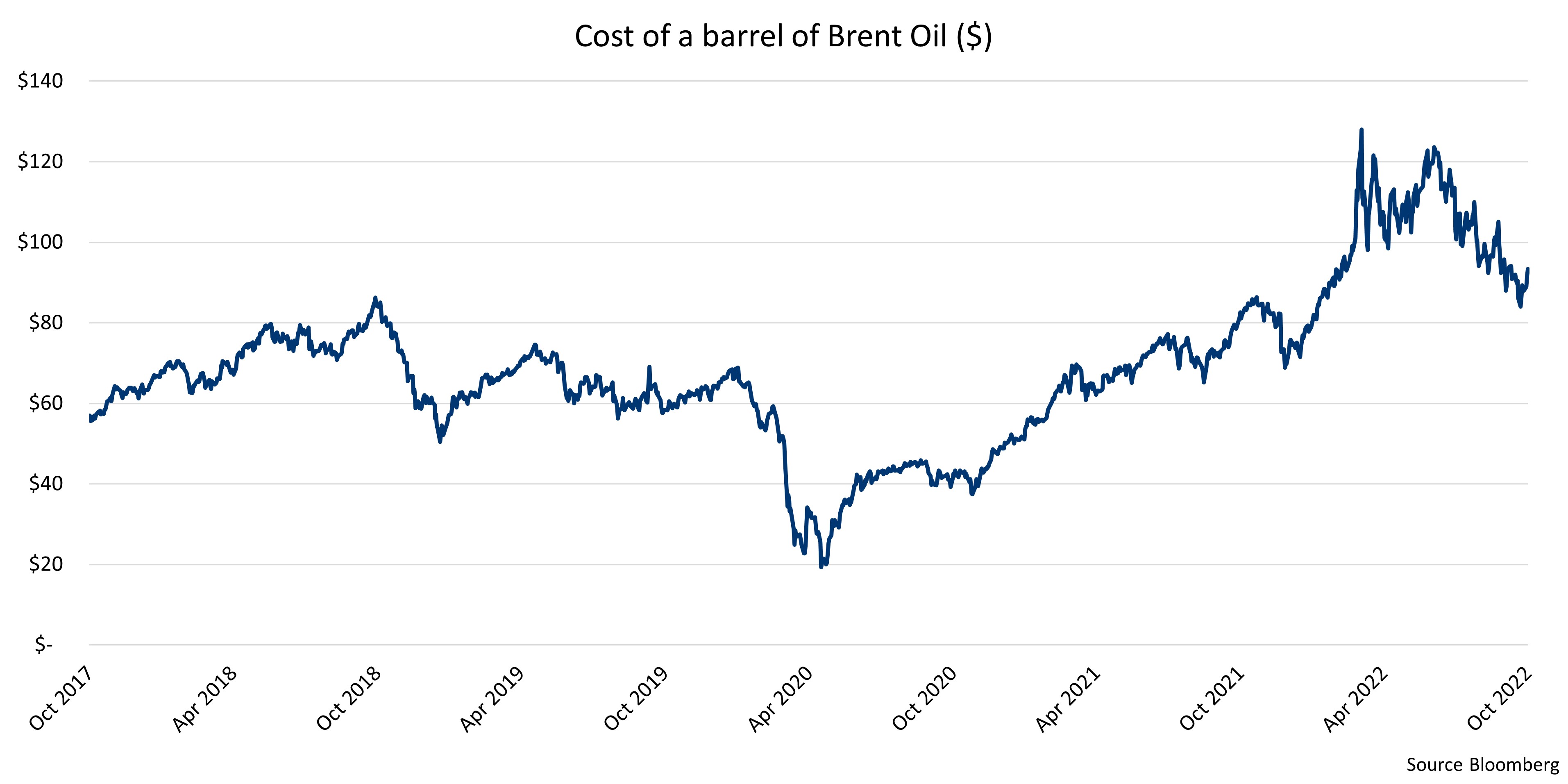

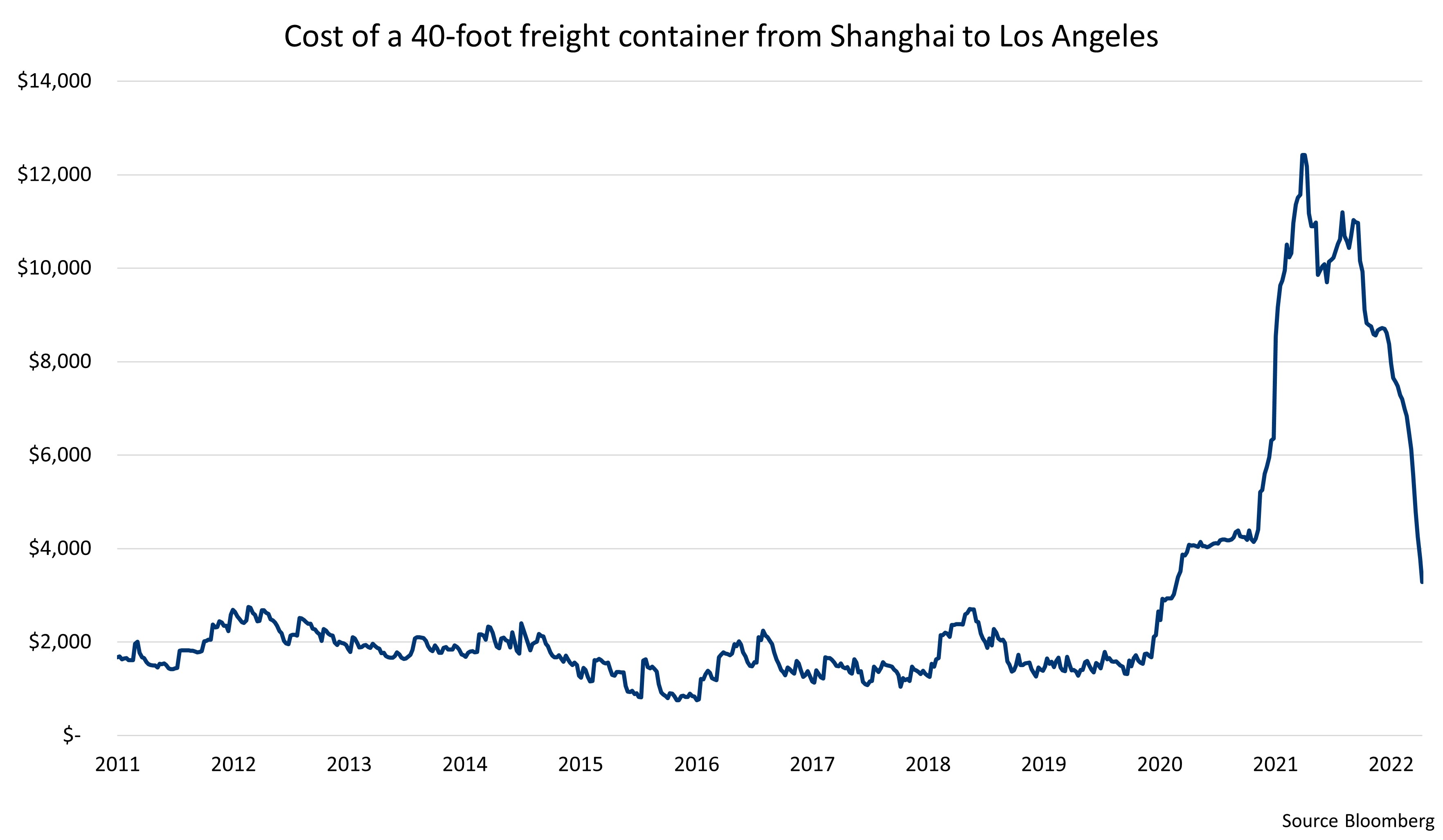

The reason we didn’t think yields would rise as sharply as they have is simply that the inflation we are currently experiencing is not a result of excess demand, it was initially due to supply-chain disruptions caused by the coronavirus lockdowns, which has since been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine – and central banks can’t control this type of inflation with higher interest rates.

In November 1971, the US Treasury Secretary, John Connally famously said, “the dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem” – and that is true again today thanks to geopolitical uncertainties (the dollar is seen as a haven which means it tends to strengthen in times of uncertainty), coupled with the fact that policymakers at the US central bank (the Fed) have stated that they intend to continue aggressively increasing US interest rates to tame inflation despite signs that the US economy is slowing.

Furthermore, compounding the problems for global financial markets is the vertiginous strength of the US dollar.

Unfortunately, this sustained strength in the US dollar has far-reaching ramifications. For example, commodities (such as oil and gas) are priced in dollars and therefore a stronger dollar makes these more expensive – which will not only hurt economic growth but will also highly likely prolong inflation outside of the US.

We believe we should start to see global inflation fall sharply over the next 12 months or so on its own volition, without the need for central banks to aggressively increase interest rates, especially given that, as you can see from the two accompanying charts, prices for oil and shipping, while still elevated, have started to soften as coronavirus supply disruptions are beginning to ease.